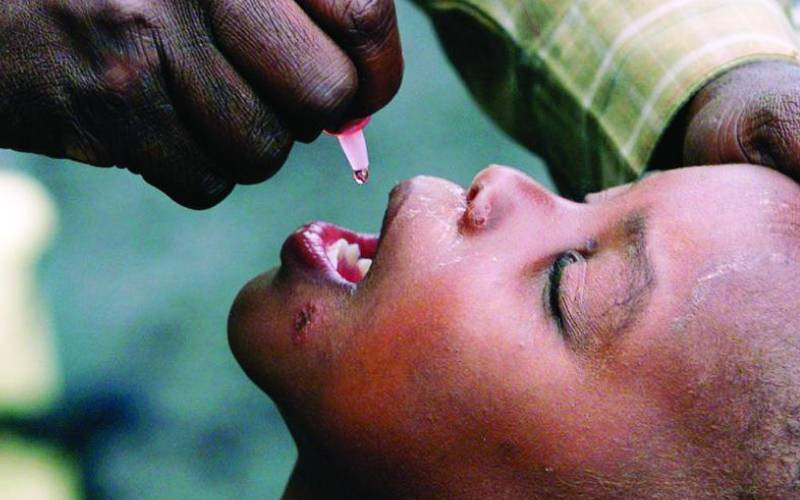

A child receives a polio vaccination at a relief camp near Gisenyi, Rwanda. [File Courtesy, AFP]

Recent media reports have highlighted a shortage of polio vaccines in Kenya, caused by several factors, including delayed disbursement of global funds earmarked for health programmes and the withdrawal of financial support by the Donald Trump administration, which had previously supported health initiatives in the country.

There are two types of polio vaccines: oral polio vaccines (OPV) and injectable polio vaccines (IPV). The question is, which vaccine is Kenya currently short of? Although Kenya has remained largely free of polio infections for nearly two decades, this success should not breed complacency. Polio has been re-emerging in neighbouring countries, such as Somalia, South Sudan, and Uganda, raising concerns about the risk of cross-border transmission.

Earlier this year, South Sudan reported new cases of polio. Occasional outbreaks have also been recorded in Somalia. These developments pose a serious threat to Kenya, particularly given the frequent movement of people across borders.

The poliovirus enters the body via the mouth, most commonly through contaminated food or water tainted with traces of human waste. After multiplying in the throat and intestines, the virus can invade the central nervous system, causing irreversible paralysis of the limbs. Medical experts warn that the virus may also attack parts of the brain and weaken respiratory muscles.

Two years ago, tests on stool samples from two paralysed children in Nigeria confirmed polio infections. Alarmingly, many adults remain unprotected against polio. The disease continues to be transmitted primarily due to poor hygiene standards, posing a significant public health challenge. Doctors note that only one in 200 polio carriers displays signs of paralysis, making detection difficult without laboratory examination of stool specimens. "Immunisation remains the most effective method to control the spread of polio. Vaccines stimulate the body's immune system to build a defence against the disease," explains Dr Mercy Njuguna, formerly of Sanofi Pasteur, a vaccine division of the Sanofi-Aventis Group.

Immunisation naturally eliminates the poliovirus from the body, confirms Dr Njuguna. Given the persistent threat of polio, the Kenyan government must intensify surveillance and ensure adequate vaccine availability across the country.

It is important for the public to be aware that injectable polio vaccines, which are primarily distributed by private pharmaceutical companies, can protect children against polio in the absence of oral vaccines. These come in pre-filled glass syringes containing single doses and serve as effective alternatives to OPV.

Dr James Nyikal, chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on Health, recently urged healthcare workers and government officials to maintain 24-hour vigilance in response to the emergence of both new and existing diseases, including COVID-19, chikungunya, Mpox, and polio. The World Health Organisation (WHO) and Unicef have pledged support to Kenya to conduct nationwide campaigns.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.