Fahiya Farah sits on a mat with her two children beneath the sparse shade of a thorny tree, in front of their makeshift manyatta. The manyatta, a simple shelter constructed from scraps of clothes and nylon sheets, is held together by ropes.

Above her, branches of the tree support an assortment of items including baby diapers, bundles of clothes, aluminum sufurias and buckets. On the ground several jerrycans are gathered ready to collect water.

Nearby, a crude enclosure made from freshly cut thorny bushes form a pen, where tens of restless goats are huddled together, eagerly waiting to be released for grazing as the intense heat of early morning begins to rise.

Fahiya, a mother of eight, gazes into the distance as she recounts the journey that led them to this desolate patch of land. She says they arrived five days ago and settled at Duhuma area of Wajir North Sub County and Wajir County.

Back home, she says, it was completely dry, and their livestock were on the brink of death due to the lack of pasture and water. They were staring at yet another potential loss.

- Health promoters overlook Christmas rest with two-month salary delay

- State boosts CHPs work with stipends, gadgets and training

- Experts: Community health promoters vital for Africa's primary healthcare

- How to strengthen malaria prevention through community

Keep Reading

“When we heard that some areas had received rain, we immediately packed our belongings and began journey with our livestock in search of that place. We travelled for five days, and as you can see, there isn’t much grass, but at least our livestock will have something to feed on for the next few days,” she begins.

Duhuma area had patches of green grass, sprouting after recent light rains. To Fahiya and other pastoralists who had arrived, it was an oasis amid the arid landscape.

Always on the go

As is the norm with a highly mobile lifestyle, Fahiya and other nomadic communities who frequently shift with their livestock for survival, have often missed or been unable to access vaccines and immunization for many years. The low immunization rates have long been a barrier to protecting children from infectious diseases, especially ones that vaccines can prevent.

Yet, the World Health Organization (WHO) describes immunization as a global health success story, saving millions of lives every year. Vaccines reduce the risk of getting a disease by working with the body’s natural defences to build protection.

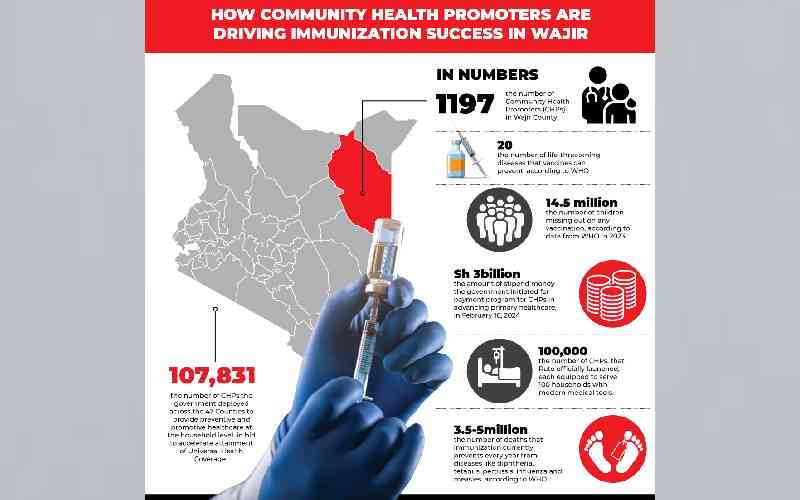

“We now have vaccines to prevent more than 20 life-threatening diseases, helping people of all ages live longer, healthier lives. Immunization currently prevents 3.5million to 5 million deaths every year from diseases like diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, influenza and measles,” WHO says.

Fahiya discloses that her eight children have missed immunizations due to constant movement with the family’s livestock in search of grass and water.

She explains, “My children have defaulted on different doses of vaccines, when forced to move due to prolonged drought. At times, you don’t find a health facility where we settle making it hard to get healthcare services.”

Luckily, three days after arriving in Duhuma, Ali Adan, a Community Health Promoter (CHP) followed the family to ensure they were in good health.

Immunisation uptake

Ali is one of 1,197 CHPs with each serving between 20 and 50 households that Save the Children and the County identified and trained in integrated community case management, including the use of Electronic Community Health System (e-CHIS), through which they input household health data.

Ali says that Fahiya’s family is one of the households he regularly visits to monitor status of their health and look for any signs of infection.

“I visit households routinely to check on their health status, ensure they are following immunization schedule and identify signs and symptoms of diseases, dangers and conditions. I treat minor ailments like diarrhoea and refer more serious cases to the health facility,” he explains.

He explains when he first started, he would encounter more than 10 defaulter cases each month. But after six months, the number had dropped to less than three, and determined to bring the number of defaulters to zero.

The CHPs have been working with the nomadic community on the move, to immunize and deliver health services to children under five especially reporting diseases such as diarrhoea, malaria and pneumonia. As a result, there has been an increase in immunization uptake in the county.

Data from WHO indicates in 2023, there was 14.5 million children missing out on any vaccination. They are called zero-dose children.

Dr John Wachira, Consultant Paediatrician at MP Shah Hospital, describes immunization as very important exercise that protects children against life-threatening infectious diseases.

“Children who have completely missed or defaulted on immunization face higher risk of infection of childhood diseases. Vaccines stimulate the body’s own immune system to protect subsequent infectious diseases,” he warns.

Aden Hujale, Project Coordinator at Save the Children highlights that nomadic communities in Wajir face significant challenges in accessing healthcare services. In some cases, they must walk between 15 and 30km to access a health facility. Given that immunization is a lifesaving healthcare intervention and a right for every child, Hujale explains Save the Children has intervened in two ways.

First, they have trained CHPs who travel with these nomadic communities to offer basic healthcare services. Secondly, they organize integrated health outreach services and support healthcare teams to travel to where communities settle, offer immunization and other healthcare services including nutrition.

“Through the CHPs, we identify children who have never received any immunization or defaulted and reconnect them to immunization services,” Hujale explains adding that to qualify as a CHP, one must be able to engage and interact with the particular community they serve.

Dispense drugs

Hussein Osman, a CHP who cares for Buna Semi-Nomadic community says they are trained to move and locate where pastoralists have settled and provide basic healthcare services.

“We were trained on technical aspects such as types of diseases we can diagnose and administer treatments. We also learned how to dispense medications, the types of drugs and correct dosages for patients,” he explains.

Osman mentions, they are trained to handle diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. They refer cases beyond their capacity to nearby health facilities.

Mustafa Abdirahman, Nurse in Charge at Malkagufu Dispensary explains that CHPs have played a critical role in increasing vaccination and immunization in the area. “Their efforts have significantly boosted immunization uptake within the community,” he says.

He explains his facility is located far from the community, making it hard for residents to access for treatment. The situation is worse when they have to migrate in search of water and pasture.

Abdirahman discloses that before CHPs were introduced in the healthcare system, Malkagufu Dispensary would vaccinate 5 to 10 children. With CHPs today, the number has increased to between 25 and 30 and continues to rise.

He explains, “In some areas, if it weren’t for the support of CHPs, no child will be vaccinated.” In addition to immunization drive, CHPs also provide healthcare education to the communities, including guidance on water treatment practises.

He adds, CHPs have helped ease the burden of overcrowding, by managing minor illnesses such as headaches.

Jamila Hussein, a CHP in Handhudera area of Wajir North Sub County takes pride in promoting and educating members of her 35 households. She, however, acknowledges that her work hasn’t always been easy, in some areas.

She shares one of the challenges was overcoming traditional beliefs that immunization could lead to other diseases or disabilities. “When l begun this work, there were areas where people believed that immunization could cause paralysis or other untreatable conditions,” she recalls.

Jamila held several healthcare education forums with her households to help them understand the importance of immunization. Today, her household members support immunization.

Sarah Abdikadir praises the CHPs who visited and advised her to take her baby to Bosicha Health and Nutrition Outreach Services, that Save the Children organizes weekly.

Initially, Sarah took her children for vaccinations at Ajawa Health Centre, which is over 15km away. Due to poor road conditions, she used to pay a motorbike operator Sh500 for transport to access the facility.

“I always take my children to get immunization, but there are times l delay due to lack of money,” she shares. She is lucky, one day, a CHP visited and informed her about the weekly Health and Nutrition Outreach Services in Bosicha, where she could take her children for immunization, without having to walk long distance or spend her money on costly transport.

Yarrow Adan, Nurse in Charge at Ajawa Health Centre explains immunization should be done right at birth, like the BCG vaccine. However, in areas without facilities there’s a lot of defaulting.

He explains, they are fortunate to have CHPs who help track and inform when a child is born. During outreach, they visit these mothers and administer required doses.

Adan, explains, previously, they had between 7 and 10 defaulters in a month during outreach. Nowadays, CHPs help in defaulter tracing and ensuring that all children receive full immunization on time.

The nurse notes some members had started refusing vaccines, fearing the pain or fever they sometimes cause to babies. But CHPs have educated the community on the importance of immunization and the disease it prevents such as tuberculosis, cured by BCG vaccines.

To improve the services further, they emphasize the need to increase the number of CHPs, that some areas are large and have only one while others don’t have.

Sanitation conditions

Mohamed Hassan, Director, Public Health and Sanitation, Wajir County explains that CHPs play a vital role in ensuring that community members receive appropriate healthcare services. They are responsible for managing minor cases and facilitating referrals cases beyond their capacity.

“The CHPs are embedded within the community and through routine home visits, identify members who need medical or specialized care. This include referring mothers in labour or those expected to deliver, in health facilities,” he explains.

They also track and record sanitation conditions in the community and report cases of diarrhoea diseases, which can serve as early indicators of potential outbreaks. In Wajir, they have been instrumental in registration of Social Health Authority (SHA).

The director explains, in terms of health, especially in nomadic communities where proper nutrition is often overlooked, CHPs are trained to assess the nutritional status of children, using tools like family Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) to screen children to identify malnutrition.

“Training for CHPs is tailored to their understanding, with focus on practical skills rather than formal education. We have training manuals designed specifically for them,” he explains.

Use of tech

Hujale explains that previously, CHPs had to carry large books for documentation such as Household Register, Service Delivery and Referral Forms, which was cumbersome and inefficient process.

Today, they use Electronic Community Health Information System (e-CHIS) to easily perform their household registration, track service delivery and submit their data to the system on a monthly basis, no matter where they are.

“The real-time data submission allows stakeholders such as Community Health Assistants (CHAs), Sub County public health officers, and County Health Management Teams to access the data and make informed decisions,” Hujale explains.

Some CHPs face challenges tracking nomadic communities as they move long distances. Jamila explains it’s costly to follow these households, especially when they travel far. “At times, I’m forced to spend my own money to reach households that have moved in different directions,” she shares. There are times when she spends nights in the bushes with families, carrying all her belongings.

Other CHPs report encountering cases that require referral to health facilities. Unfortunately, many lack the means for transport. “At times, we have to pay for their transport, whenever possible,” Osman shares.

However, Adan, Nurse in Charge at Ajawa Health Centre, assures that emergency cases are addressed. When such cases arise, the health facility sends a team or an ambulance to transport the patient for treatment.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.