A matured Loggerhead Sea turtle released by staff from Local conservation makes its way back into the ocean, in Watamu on May 23, 2025. [AFP]

A small charity on Kenya’s coast has become vital to protecting the region’s majestic turtle population, saving thousands from poachers, fishermen’s nets, and worsening plastic pollution.

On the beach in the seaside town of Watamu, it took four men to lift a large Loggerhead Sea turtle into the back of a vehicle. The turtle had just been rescued from fishing tackle and was taken to a nearby clinic for injury checks, then weighed, tagged, and released back into the sea.

Local Ocean Conservation (LOC), a Kenyan NGO, has been carrying out this work for nearly three decades, completing around 24,000 rescues. “Every time I release a turtle, it’s a great joy for me. My motivation grows stronger with each rescue,” said Fikiri Kiponda, 47.

LOC began in 1997 as a group of volunteers appalled by seeing turtles being eaten or trapped in nets. Despite efforts, turtles are still poached for their shells, meat, and oil.

However, through the charity’s awareness campaigns in schools and villages, “perceptions have significantly changed,” explained Kiponda.

Mostly relying on donations, LOC compensates fishermen who bring in injured turtles. More than 1,000 fishermen take part in the scheme, motivated mainly by conservation rather than financial gain, as the compensation does not fully cover lost working hours.

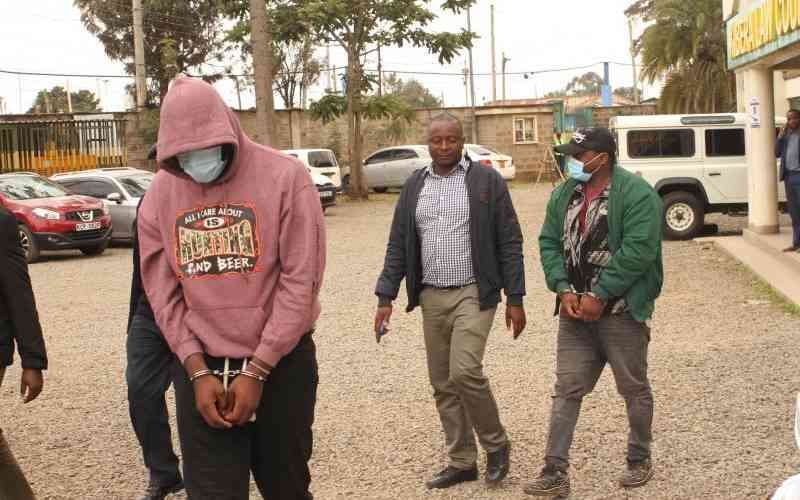

Staff from Local Ocean Conservation and fishermen lifting a mature Loggerhead Sea turtle into a car, to be taken to observation in the rehabilitation centre before being released back into the ocean, in Watamu on May 22, 2025. [AFP]

At LOC’s clinic, health coordinator Lameck Maitha, 34, said turtles are often treated for broken bones and tumours caused by a disease called fibro papillomatosis.

One current patient is Safari, a young Olive Ridley turtle around 15 years old. Turtles can live for over 100 years. Safari was transported by plane from further up the coast in critical condition, with a bone protruding from her flipper that had to be amputated, likely caused by struggling to free herself from a fishing net.

Safari is recovering well, and the clinic hopes to release her back into the ocean.

Plastic pollution poses an increasing threat. When turtles ingest plastic, it can cause blockages that generate gas, making them float and unable to dive. In such cases, the clinic administers laxatives to clear their systems.

LOC also protects 50 to 100 nesting sites, threatened by rising sea levels. Turtles travel far, but always return to lay eggs on the beach where they were born — Watamu being a key site.

Marine biologist Joey Ngunu, LOC’s technical manager, affectionately names the first hatchling to emerge each season, Kevin. “Once Kevin appears, the rest follow,” he said, describing their slow journey to the sea at night to avoid predators. Only one in a thousand hatchlings reaches adulthood, which can be between 20 and 25 years.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter