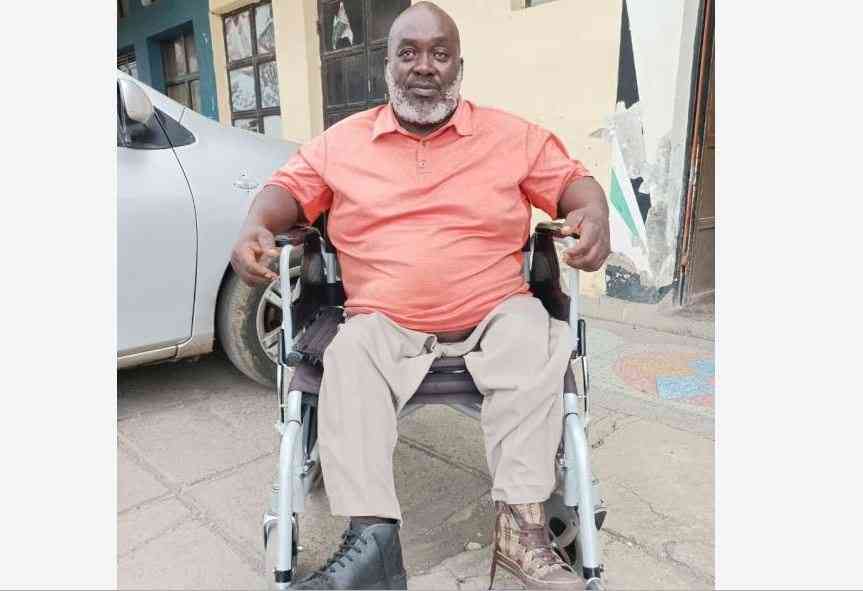

Harold Kipchumba knows what it means to live with the consequences of missed vaccines. A polio survivor, his painful journey has made him one of the most passionate advocates for immunisation.

In an in-depth interview with The Standard on Sunday, Kipchumba recounts how he met the Gavi team and other stakeholders while championing accountability over misappropriated funds.

In 2018, as an immunisation ambassador, he helped appoint polio champions in every county to monitor the system. He also supported the rollout of cold-chain monitoring systems and a national programme to track children receiving vaccines at health centres.

Thanks to the programme, immunisation coverage for newborns rose from 40 to 80 per cent.

Kipchumba also recalls the early days of the Beyond Zero Campaign in 2013, when he and then First Lady Margaret Kenyatta led parallel efforts to improve maternal and child health.

Mrs Kenyatta focused on maternal and child health, while Kipchumba led the immunisation campaign.

Through a polio programme supported by UNICEF, WHO and other stakeholders, Kipchumba developed a powerful concept driven by survivor stories. However, the programme was scrapped by the current administration after it failed to allocate a budget, making it difficult for donors to continue their support.

Today, he watches with heartbreak as the country risks reversing decades of progress in vaccination—especially if Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, follows through on its threat to withdraw support.

“Our biggest problem as a country is a political mindset,” Kipchumba says. “We are expected to sustain ourselves at both national and county levels, but very little is invested in immunisation. We will suffer more.”

Kipchumba recalls the impact of the now-defunct immunisation programme: “It was working. We had a clear system. If freezers or vaccines were needed, we had mechanisms to respond. But when the programme was scrapped, no one followed up. Now, if BCG or other vital vaccines are missing in clinics, it’s the community that raises the alarm while the government remains silent.”

He warns that Kenya is becoming increasingly vulnerable due to the failure to fund, monitor and prioritise immunisation.

Kipchumba questions the government’s commitment. “Is there even a fully established, well-funded immunisation office? If it’s just an annex in another department, it won’t survive. Without a strong structure, many children will miss out—newborns will suffer in silence.

His outlook on the future of vaccination in Kenya is bleak.

“It’s grim. We already have vaccine shortages in some regions, and response times are too slow. Even when vaccines arrive, no one checks on the children who missed them. That’s how outbreaks resurface. We’re seeing cases of dysentery again.”

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

He emphasises the urgency. “Vaccines are not like meals you can delay. If a child misses that critical window, the damage is done. It scares me—old diseases like measles, TB, and dysentery are creeping back. If we don’t act, by 2027 or 2029, we’ll face a major health crisis.”

“Children don’t choose to get vaccinated. That decision lies with parents, health workers, and leaders. When they fail, a child pays the price. I live with that reality.”

He pleads with Gavi not to abandon Kenya just yet.