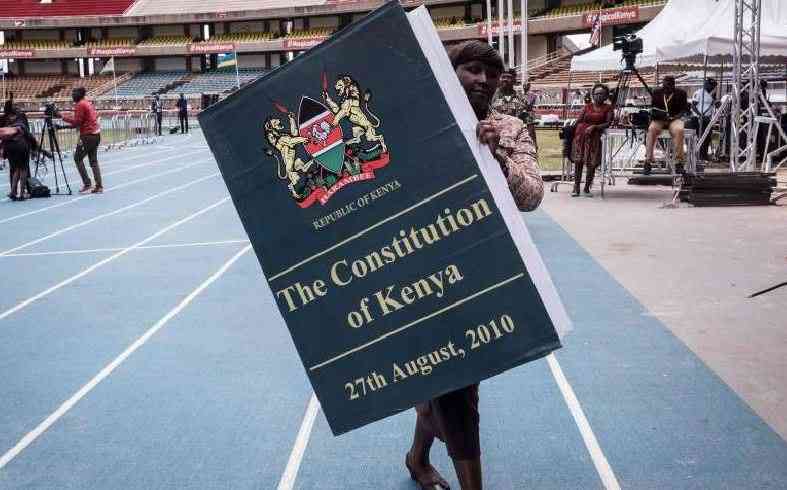

The Constitution of Kenya is often described as one of Africa’s most progressive charters, a document born out of struggle, sacrifice, and the people’s collective yearning for justice. It envisions a society governed by equity, human rights, and the rule of law. Yet, for this vision to truly live, the legal profession, the guardians of justice, must embody the Constitution’s transformative spirit. Kenya urgently needs a legal profession that believes in social engineering, one that sees law not as a tool for privilege. To the contrary, as an instrument for reshaping society toward fairness and inclusion.

Law, as the late American jurist Roscoe Pound argued, is a form of social engineering, a means of balancing conflicting interests for the greater social good. In Kenya, this philosophy is not merely academic. It lies at the heart of our constitutional promise. Article 10 demands adherence to national values such as human dignity, equity, and social justice. Article 159 vests judicial authority in the people, emphasising that justice shall not be delayed or denied on technicalities. And yet, these noble principles risk remaining hollow rhetoric unless the legal fraternity commits to advancing them beyond courtroom formality.