Fraud is a global problem, affecting organisations across every region and industry worldwide. Governments lose hundreds of billions of dollars annually to corruption and fraud, with the US government estimated to lose about $233 billion each year.

In Kenya, former President Uhuru Kenyatta once said the country was losing approximately Sh2 billion every day to corruption. A few years ago, while attending an investor conference in Washington, DC, I struck up a conversation with a fellow attendee during a break. Upon learning that I was from Kenya, he remarked, “It is a great country with great people and enormous potential, but very poor governance and runaway corruption that chokes business opportunities.”

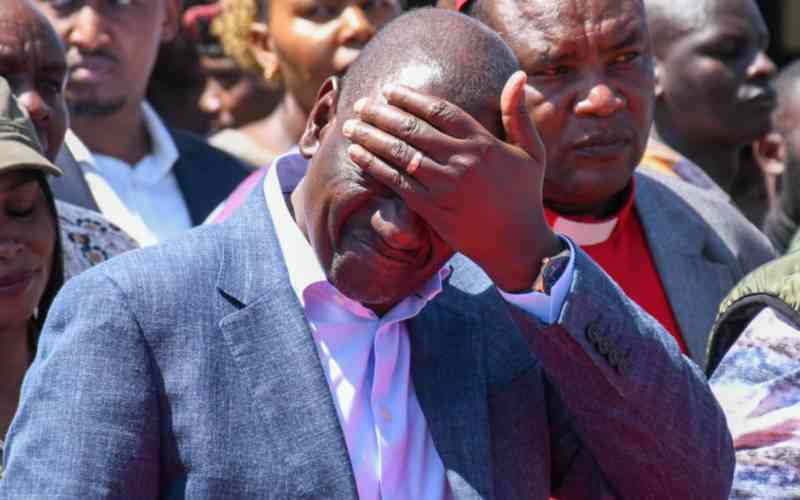

That candid observation captures Kenya’s dilemma with painful accuracy. While corruption in Kenya exists at all levels of society, it is grand corruption by political elites and senior government officials that has brought the country to its knees. A privileged few, perhaps the top five per cent are responsible for vast majority of corruption, siphoning trillions of shillings from public coffers with near total impunity.

This reality raises an uncomfortable question: why do already wealthy and privileged individuals continue to steal? The answer lies partly in the Fraud Triangle, a theory developed by criminologist Donald Cressey. It explains fraud as the convergence of pressure, opportunity, and rationalisation. In Kenya, all three are abundantly present at the highest levels of power.

Pressure among elites is not driven by poverty, but by greed, peer competition, and societal expectations. Public officials are expected by themselves and by society to display extravagant lifestyles. During recent Cabinet confirmation hearings, many nominees declared net worth ranging from hundreds of millions to billions of shillings. The unspoken message is clear: to belong in political circles, one must be enormously wealthy, regardless of how that wealth is acquired.

Opportunity, the most controllable element of fraud, is where Kenya fails most dramatically. Weak institutions, compromised oversight bodies, ineffective internal controls, and political interference have created an environment where corruption is easy and largely risk-free. From the Goldenberg scandal to Eurobond and SHA-related losses, trillions have vanished without a single high-profile conviction or meaningful asset recovery. This long history of impunity has normalised grand theft of public resources.

Rationalisation completes the triangle. Corrupt actors convince themselves that “everyone is doing it,” that public money belongs to no one, or that they are entitled to it.

Kenya’s institutions, constitutionally mandated to fight corruption, have largely failed.

If Kenya is serious about fighting corruption, reforms must begin at the top. A zero-tolerance approach is essential. Any public official indicted on corruption charges should be placed on administrative leave until their case is resolved. Corruption cases must be fast-tracked, and those found guilty should face severe penalties, including permanent exclusion from public office. The President must lead by empowering anti-corruption agencies and shield them from political interference.

The writer is a budget expert in Washington DC. [email protected]