“Whoever molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes, or pronounces judicial decisions.” - Abraham Lincoln

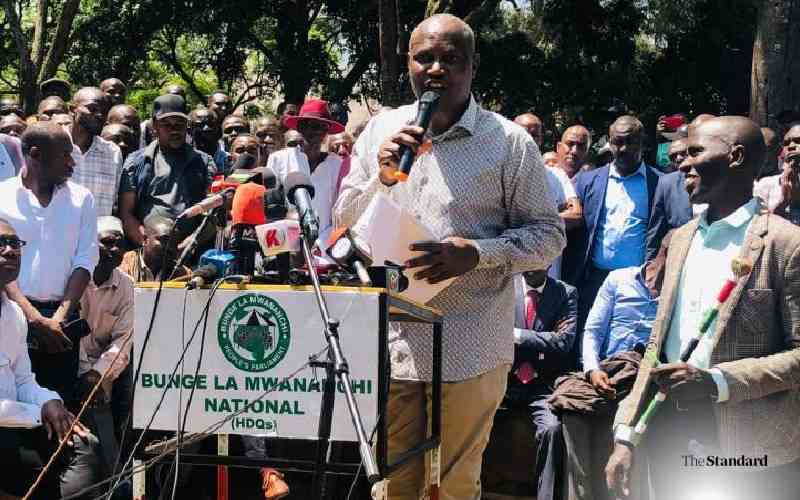

It was a pleasant surprise seeing the Cabinet Secretary for The National Treasury and Economic Planning Mr. John Mbadi engaging citizens at Jivanjee Gardens, the venue of the Bunge la Mwananchi.

The issues the citizens address at this forum are topical. All that they discuss have bearing on the safety and wellbeing of the country.

They look at the policy actions of the government in light of how far they go in enhancing the safety and wellbeing of the people, and minimizing the risks and dangers that might happen.

That Mbadi walked to the Jivanjee Garden straight from an interview with a local TV station was an act of courage. It was an act of courage because there is normally no structure, no self-imposed constraint at such forums. People think and speak on issues without fear. This can make a person who is unprepared, trip.

The faceoff the Cabinet Secretary had with the “members” of Bunge la Mwananchi was public participation par excellence. It stood out as the most genuine expression of public participation in recent times. It surpassed many of the so-called “public consultations” that rely on formal invitations through newspaper advertisements. What the government ends up having during formal occasions are representatives of civil society, Community Based Organisations (CBOs), non-governmental organisations all of which are financed by foreign interests.

I often find most of the engagements distant and inaccessible to the very people it seeks to engage and who feel the exhilaration and the pain of the public policy issue, and problem the government wants fixed.

Watching Mbadi speak, one cannot help but feel a deeper connection with public sentiment and a feeling that the public felt heard. I haven’t heard complaints that the people the CS met were not presentative or the issued they raised with the Minister were offkey.

Today, such situations are rare. Situations where leaders of government informally connect with ordinary citizens at such a personal level.

It wasn’t always like this.

Long before public participation was enshrined in the Constitution, the administration of the Presidency of the late Daniel Moi had already mastered the art of grassroots engagement.

His administration cultivated a culture where government officials didn’t just sit in offices but went out to the people.

Under the leadership of the Provincial Administration, heads of government departments at the grassroots visited the field on three occasions.

First, on a regular basis. Authorities met the wananchi, mainly in market centres but after the District Commissioner, had toured projects (miradi as they were called), where he held a baraza.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

With all the heads of departments present, the residents were allowed to speak first before the District Commissioner spoke. The residents raised issues and problems that hindered their safety and welfare. The District Commissioner then permitted the heads of departments to respond to the issues relevant to their dockets. The District Commissioner was always the last to speak, as the guest of honour.

Here was the government engaging with the citizens. It was through these occasions that the government understood came evaluating the pulse of the citizens on the burning issues and questions of the day.

The District Information Officer, under the auspices of the Kenya News Agency (KNA), was always present to capture the sentiments of the people and the policy positions or actions the government was taking or would take on an issue, a problem or risk facing the community. The officer filed stories to this effect to KNA newsroom at Information House on Mfangano Street for dissemination to Kenya Broadcasting Corporation and other media outlets.

The second occasion when the government got in touch with wananchi was when a government department was celebrating something either peculiar to the district or the nation.

Take, for instance, the education sector. During Provincial Education Days, the Cabinet Secretary (then Minister) would meet students, teachers, and parents on their turf. This was during special occasions called Divisional, District or Provincial education days. During these occasions, officials explained the various aspects of education the government was undertaking to provide education services to wananchi.

These were not scripted interactions but genuine engagements where the public could voice their concerns directly.

The Minister or his representative, would listen attentively on education matters, performance and issues raised by different leaders including students’ entertainment, the Minister would, at the end, make policy pronouncements informed by the raw, unfiltered conversation of the people.

People went home happy. The minister met headteachers, teacher unions, officials of District Education Boards (DEBs), area members of Parliament at one locale. He maximized his visits to any region, province or district.

The Ministry of Agriculture had a similar model. We had what they call Agricultural Field Days, across the country and at District levels. I don’t know if Agricultural and livestock shows weren’t just exhibitions—they were major policy forums where farmers, industry experts, and government officials deliberated on the challenges facing the sector. These forums were inclusive, drawing participation from the very communities whose livelihoods depended on the outcomes of these discussions.

The Ministries of Health, Water, Environment etc. had their special days. The government was always on toes—interacting with the people. Kenya News Agency staff was always there—of course with reporters from the private media. To report the issues peculiar to the days and occasions.

The third and by no means the least occasions the government met the people was when there was a crisis or a problem threatening the safety and wellbeing of the residents of a place or an institution.

You would see the presence of the government almost simultaneously. You would see the District Commissioner with his entourage at the point of trouble.

In the entourage would be technical officers relevant to the problem at hand. Depending on the problem, the technical officers may have come earlier to contain the trouble—but have the district commissioner the face of the Government to address the affected people. If the problem has caused damage to life and property on a wide scale, you would see the Minister concerned at the scene of the problem.

You’re gonna be with the people during life threatening situations. Experts in crisis management say, communication is presence, empathy and assurance. That is public participation par excellence. I don’t need to say that the KNA was present to tell the story.

That was then. Today, the shift towards press statements. Facility visits. Media especially invited me. The very people most affected by government policies are often left out of these rigid, bureaucratic procedures.

Mr. Mbadi’s decision to walk to Jivanjee, after a TV show some 200 meters away, was refreshing. It was a reminder that true public participation happens where the people are— in open spaces where leaders and citizens can engage freely, candidly, and meaningfully. Not in conference rooms or through newspaper notices.

It is time we reconsider how we define public participation. It should not be a mere formality or a checkbox in governance. It should be a dynamic, ongoing conversation—one that is rooted in authenticity, accessibility, and true representation of the people’s voice.

To do this a structure needs to be in place that informalizes the process as much as possible to make it more authentic. Yes. Citizen-centred management of public affairs. There is little room for misunderstanding, misinformation or disinformation.

Then defunct Ministry of Information and Broadcasting had an average of five Information Officers in every District to publicise government policies, programmes, projects and initiatives as articulated from time to time, by government officials.

The Ministry had also deployed experienced staff in all Ministry headquarters. It acted as an important link between the government and its people.

The government information and communication service are needed more than ever before. It needs to be strengthened.