Growing up in the rolling hills of Nyandarua County, Hannah Chege’s childhood was defined by early mornings spent helping her father care for their small herd of dairy cows.

For her family, these cows represented more than just livestock; they were a vital lifeline. The milk they produced covered school fees, provided food on the table, and formed part of their daily life.

However, this delicate balance was often threatened by a deadly intruder: East Coast Fever (ECF). Hannah recalls the anguish in her father’s eyes when one of their cows fell victim to the disease—a single loss that could jeopardize their finances and leave them vulnerable.

These formative experiences ignited Hannah’s profound curiosity and determination to understand the disease that jeopardized her family’s livelihood.

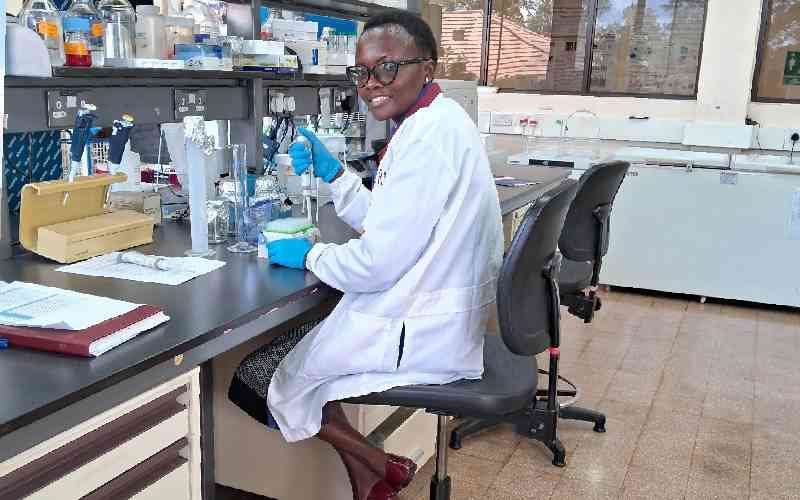

Today, as a PhD student at the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Animal Health at the University of Nairobi’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Hannah is channeling that childhood determination into groundbreaking research to mitigate ECF.

Her journey from handpicking ticks on her father’s farm to working in state-of-the-art laboratories embodies a profound commitment to protecting her family’s legacy and the livelihoods of millions across Africa.

East Coast Fever, often called the ‘malaria of the cows’ in some parts of of the country, is a fatal cattle disease that profoundly impacts the community. The disease is caused by Theileria parva, a parasite spread by ticks. This disease is estimated to kill over a million cattle annually, significantly reducing the income and food supply of families who depend on livestock.

“When we were young, part of our responsibilities when the animals were grazing in the fields was to handpick the ticks because our father had told us they were causing a deadly disease. It was only later, when I joined the Veterinary School that I realized it was ECF,” she says.

Alternative vaccine

Farmers in Nyandarua County refer to the disease as ‘Ngai’ in their language. It is a top killer of their calves.

Her PhD research at the University of Nairobi, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Parasitology has focused on developing a Subunit vaccine against the disease. She uses the antigen, a protein part of the parasite that causes severe disease, to develop the sub unit vaccine.

Through this, they hope to eliminate antibiotic use, which may lead to antimicrobial resistance in animals, humans, and the environment. Hanna explains that the disease is controlled by a live vaccine, called the Infection and Treatment Method (ITM), which uses a live parasite given to a healthy animal concurrently with an antibiotic to prevent development of severe disease.

Among the limitations of the current vaccine is that it requires cold-chain storage, mainly liquid nitrogen, which may not be available in some rural areas. The vaccine is also expensive, takes a long time to manufacture and must be administered by a qualified personnel. Therefore, in her research, Hannah has been working on alternative affordable vaccine (sub-unit) to overcome the limitations of the ITM vaccine.

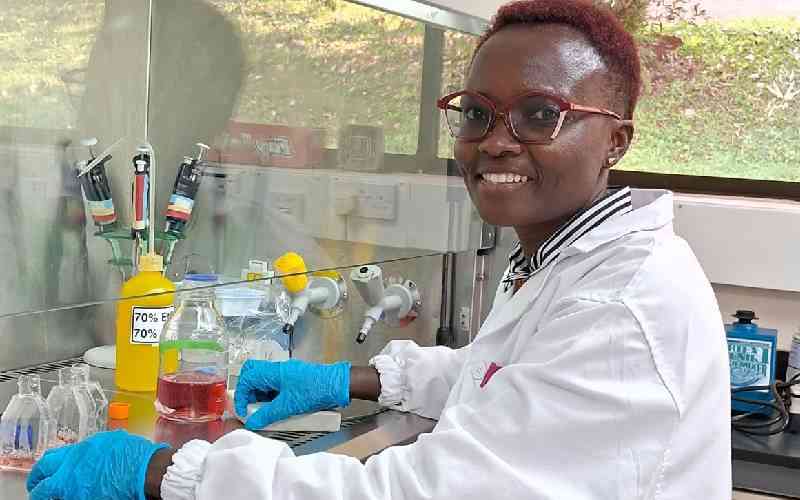

She used computer-based analysis to study scientific information about Plasmodium falciparum (a parasite that causes malaria) and Babesia bovis (both of which are related to the parasite that causes the disease). This research helped her discover proteins/antigens in these parasites that work in similar ways and could be used to develop a sub-unit vaccine for ECF.

From her findings, she identified four new proteins/antigens from T.parva and used them to vaccinate cattle, successfully triggering an immune response. She then collected blood from the cattle, extracted the serum containing antibodies, and tested how well these antibodies could block the infection-causing parasite (T. parva sporozoites). This work identified six promising vaccine candidates—a “cocktail” of four newly discovered antigens and two previously known ones—that could potentially protect cattle from ECF.

She explained that getting her results would take long incubation period of about 12 days; if one failed, it would have to be repeated, which would take another long time. “Also, working with the sporozoites was not easy because they died very easily because I was using the frozen material,” she adds.

Improve nutrition

This was coupled with the great support she received from her mentorsat the University of Nairobi, for which she is very grateful.

Hannah is one of the 10 fully supported PhD fellows under the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Animal Health (AHIL) program.

This program, implemented in 600 households in Narok County, aims to improve human nutrition, economic welfare, and resilience by removing cattle health and production constraints. It provides support and resources for researchers to conduct their studies and make a significant impact.

Building hope

Washington State University leads the AHIL consortium through Prof Thumbi Mwangi, which includes Kenya-based partners, including the University of Nairobi, the International Livestock Research Institute, scientists from the Kenya Medical Research Institute, and the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KARLO).

The five-year program combines laboratory and field intervention studies to improve the uptake of animal health interventions and measure the impact on household well-being and the nutritional status of women and children.

When Hannah isn’t meticulously analyzing samples in the laboratory, she finds solace in travelling and discovering her rural home’s open landscapes. With her scientific expertise and deep connection to farmers’ struggles, Hannah envisions a future in which ECF is no longer a death sentence for cattle or a financial catastrophe for families.

“The look on my father’s face every time one of our cows fell ill and died from ECF gets me going. I have seen how this disease can lead to substantial loss, and my commitment to continue this work—not just in the lab, but alongside farmers in the fields where I grew up,” she says with determination. With resilience, science, and compassion, Hannah isn’t just fighting a disease—she’s building hope, one cattle farm at a time.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.