For over 15 years, Gilbert Aduda endured excruciating back pain that robbed him of even the simplest joys of life.

A retired radiographer from Kochia West in Homa Bay, Aduda could no longer sweep his house, bend, or walk short distances without feeling as if his spine were on fire. “Even lifting a broom was unbearable,” he recalls, his voice heavy with emotion.

The pain became a constant companion. Painkillers offered only temporary relief—once the tablets wore off, the agony returned with greater intensity. “I didn’t know whether the problem was getting worse or better,” he says.

Despite years of follow-ups, the pain only intensified, until July this year, after yet another desperate clinic visit, when his doctor ordered a new MRI scan. The results were devastating: the nerves between his lumbar vertebrae—L2 to L5—were being compressed, a condition known as lumbar stenosis. The degeneration had progressed to the point where surgery was the only option.

His doctor referred him to Dr Lee Ogutha, the only resident neurosurgeon at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH) in Kisumu.

Dr Ogutha was preparing for the September neurosurgical camp, organised in partnership with the Kisumu Neuroscience Initiative. For Aduda, the timing felt providential.

With help from his daughter, who works at JOOTRH’s primary care unit, Aduda was screened and scheduled for surgery during the camp, held from 8th to 18th September. Despite warnings from friends and neighbours who feared spinal operations, his medical background gave him the confidence to proceed. “Many people said surgery would leave me in more pain. But I told them, even without surgery I’m already in pain and can’t walk properly. It’s better to try the operation and give the nerves a chance to recover,” he says.

- Jaramogi Oginga Odinga hospital hits another milestone after elevation to parastatal

- Risks of dismissing back pain during pregnancy

Keep Reading

Last week, Aduda underwent surgery. For the first time in over a decade, he woke up without the crippling pain that had ruled his daily life. “I feel relieved. What I feel now is just mild surgical pain. The unbearable pain is gone. I’m hopeful I can return to a normal life,” he says with a faint smile.

The neurosurgical camp that gave Aduda a second chance is now in its seventh year. According to JOOTRH’s acting CEO, Joshua Clinton Okise, the camp is part of an ongoing collaboration between the hospital and volunteer neurosurgeons from Kenya and abroad. “This initiative began several years ago as part of corporate social responsibility. It’s become a lifeline for patients with spinal, trauma, and other neurosurgical conditions,” says Okise.

Competent team

Held twice a year in April and September, the one-and-a-half-week camp screens patients at JOOTRH’s neurosurgical clinic before selecting those eligible for surgery.

Since its inception in 2018, the programme has delivered more than 500 life-changing operations. “This year, we aim to operate on 34 to 48 patients. The team, both local and international, is highly competent and committed. The surgeries are free of charge, patients only need to be registered with the Social Health Authority (SHA) to qualify,” Okise says.

He emphasises the camp’s significance for the region; “Here, we only have one neurosurgeon, Dr Lee Ogutha. Most neurosurgeons are based in Nairobi, making it difficult for patients in western Kenya to access this level of care. Through this camp, many people in the Lake Region benefit directly.”

Among the visiting specialists is Dr Bethwel Raore, a neurosurgeon based in Atlanta, Georgia, and co-founder of the Kisumu Neuroscience Initiative.

Born in western Kenya and a former student of Maseno School, Dr Bethwel Raore left the country after high school—but never forgot his roots.

“When I first visited JOOTRH in Kisumu in 2017, there was no neurosurgeon in the region. I thought one of the most meaningful things a Kenyan in the diaspora can do is give back. So, together with two other diaspora neurosurgeons, we formed the Kisumu Neuroscience Initiative. Our goal was to provide neurosurgical care, to teach, and to inspire the next generation,” he recalls.

The initiative now runs three medical camps a year, offering specialised surgeries that would otherwise be out of reach for many Kenyans. “Since 2018, we’ve done over 500 surgeries. We’ve had excellent outcomes. The camp is now well known, and patients travel from across the country,” says Dr Raore.

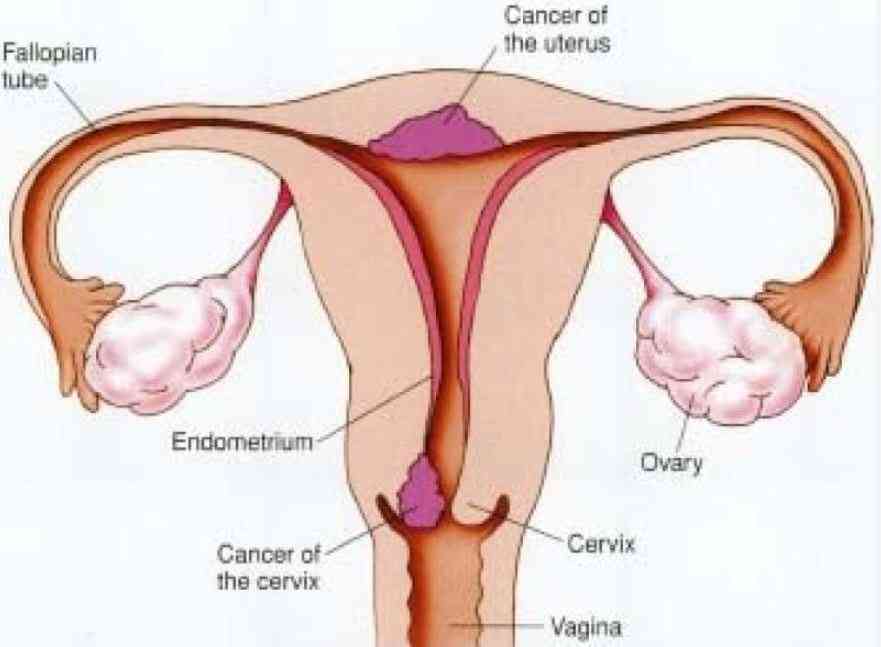

Gilbert Aduda was diagnosed with lumbar stenosis, complicated by facet arthropathy. Dr Raore, who led the surgery, explains: “Lumbar stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal, which compresses the spinal cord and nerves. Facet arthropathy is the degeneration of the facet joints, worsening the compression. For Gilbert, the pressure made even basic movement excruciating.”

He underwent a laminectomy, where part of the vertebra is removed to relieve nerve pressure. “It’s a standard procedure, and Gilbert’s surgery went smoothly,” Dr Raore notes.

He adds that surgery is always the last resort. “We start with painkillers, physiotherapy, sometimes injections. But when these fail, surgery becomes necessary.”

Beyond the operations, Dr Raore highlights the camp’s wider purpose: training local doctors, residents, and students from Maseno and Uzima universities. “We want neurosurgery in Kisumu to become routine, not rare.”

Back pain, the condition that nearly crippled Aduda—is a global health issue. According to the World Health Organisation, over 619 million people worldwide had low back pain in 2020, a number expected to reach 843 million by 2050. It remains the leading cause of disability globally.

The burden peaks between ages 50 and 55, with women more likely to be affected. While many cases resolve in weeks, others become chronic, limiting movement, work, and social life.

Facet arthropathy, one of the causes of lumbar stenosis, is essentially arthritis of the spine. It occurs when the facet joints that provide stability and flexibility wear down due to age, obesity, or lifestyle. Symptoms include dull, aching pain, stiffness, and pain that worsens after long rest, twisting, or bending backward.

“When the spinal canal narrows because of facet degeneration, patients develop lumbar stenosis,” notes the WHO.

“Symptoms include back pain, burning pain down the legs, numbness, cramping, and weakness. Relief often comes from sitting or leaning forward.”

For Aduda, the difference is already evident. Though still recovering from surgery, he reports marked improvement. “The severe pain is gone. I believe it was successful. Even the things I could not do, I know I will do them now,” he says with optimism.

Widowed in 2020, he lives alone, but his six children have been his greatest support system. During his illness, his younger brother often helped with chores, while food was prepared at his brother’s home. “At times I felt helpless,” he admits. “But now I feel I have my life back.”

As he begins physiotherapy, he looks forward to reclaiming independence. “Even sweeping my own house will mean a lot. I know many people fear surgery, especially on the spine. But I would tell them when medicine no longer works, surgery can give you a second chance.”

For each, the operation represents not just medical treatment but restored dignity and renewed hope.

For Aduda, a man who endured 15 years of torment, it is the beginning of a new chapter.

“I am grateful,” he says softly. “Life is coming back to normal.”

According to Dr James Obondi, an orthopaedic surgeon at OOTRH, the lumbar spine is the most affected region as it bears the body’s greatest load and allows mobility.

“The lumbar spine supports the weight of the head, chest, and upper body before it transfers to the legs. Over time, this stress causes wear and tear, particularly to the discs between vertebrae,” he explains. “These discs act as cushions, but they can compress and leak fluid, pressing on nerve roots and causing severe pain, numbness, or a burning sensation down the legs.”

Dr Obondi cites the case of Aduda, saying an MRI revealed severe nerve root compression and narrowing of the spinal canal—a condition known as spinal stenosis. Surgery became the only viable option.

“We recommended a laminectomy to relieve pressure on the nerves,” says Dr Obondi. “Surgery is never our first solution—it’s the Supreme Court of treatment. Before reaching that stage, we try painkillers, physiotherapy, and epidural injections. But in Aduda’s case, conservative options had failed.”

Causes of low back pain vary with age and lifestyle. Among older adults, lumbar spondylosis—age-related degeneration—often leads to bony growths (osteophytes) that press on nerves. In middle-aged adults, disc bulges are common, linked to heavy lifting, prolonged sitting, or computer use. Even children may develop “schoolbag syndrome” from carrying heavy bags daily.

Some groups face higher risks. Intravenous drug users may develop spinal infections. Cancer patients can suffer back pain if malignancies such as multiple myeloma, prostate, or breast cancer spread to the spine. “We must thoroughly investigate all cases, especially in older patients, to rule out tumours,” Dr Obondi emphasises.

Back pain, he notes, is a universal problem. “Even in the US, it’s the top reason people miss work. In Kenya, lifestyle and occupation play a big role—farmers bending all day, long-distance drivers, and office workers are all vulnerable.”

While breast or prostate cancer often causes back pain in the West, in Kenya, disc-related complications are more common, particularly among women. In Kisumu, spondylosis is the dominant diagnosis, especially in older women.

Lifestyle and diet are key to prevention and management. “Sedentary lifestyles lead to early back problems. In the Rift Valley, older people remain active—running, climbing hills, farming—and rarely develop these issues. In Kisumu, inactivity contributes significantly,” says Dr Obondi.

He adds that smoking, alcohol, and poor diet increase the risk. “Those who eat more vegetables and live active lives tend to report fewer cases than heavy meat eaters or those with poor habits.”

For post-surgery patients, discipline is essential. “Avoid bending, lifting heavy items, or twisting the back for at least six months. No weightlifting, head-loading, or intense dancing. Physiotherapy must be followed strictly for full recovery,” Dr Obondi advises.

Despite progress, he acknowledges that gaps remain in facilities and resources for managing complex spinal conditions. However, initiatives like the JOOTRH neurosurgical camp have made specialised care more accessible.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.